Dock 72 at the Brooklyn Navy Yard is the latest addition to WeWork’s portfolio of shared working spaces. Unlike most WeWork locations, this one was built from the ground up—in conjunction with Boston Properties and Rudin Management Co. Situated between DUMBO, Williamsburg, and Downtown Brooklyn, Dock 72 is accessible to all commuters. Those coming from Astoria, Midtown, and Wall Street will be able to access Dock 72 from its own dedicated ferry stop.

In addition to the typical WeWork amenities—like scenic views and multiple terraces—the building will also include a food hall with stations curated by Danny Meyer and 10,000 square feet of outdoor space, which features two Civil War–era cannons that were unearthed during construction. The 16-story building, surrounded by water on three sides, was intentionally built on columns, so that it will withstand flooding in the event of a major storm.

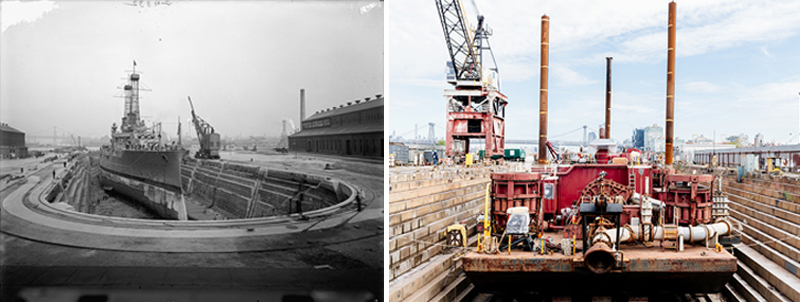

The site—formerly a dry dock—features a unique history as the birthplace of many of the Navy’s most iconic and technically innovative ships, which fought in every major conflict from the Civil War to World War II. There was the USS Monitor, built in 1861 and used against the Confederacy’s CSS Virginia in the 1862 Battle of Hampton Roads, which was the first time two ironclad warships faced off against each other. Although the battle’s results were somewhat inconclusive, militaries around the world rushed to copy the Monitor’s ironclad design and turret that could fire in every direction.

Do you “Remember the Maine”? That was the battle cry of the Spanish-American War, inspired by the loss of the USS Maine, a Navy Yard–built battleship that sunk in Havana in 1898 and catalyzed the Spanish-American War. The debate over the cause of the ship’s sinking still simmers—the official story was that a Spanish mine caused the explosion, while the Cubans argued that the U.S. government sunk their own ship as a pretext for war. At the time, warring newspapers amplified conspiracy theories to boost readership, a 19th-century prelude to today’s “fake news” era.

And finally, there was the USS Arizona, considered to be the most powerful ship ever built when it launched from the Navy Yard in 1916, at a cost of $16 million. But it met a tragic end: After remaining stateside for World War I as a training facility, it traveled to Hawaii, where it was bombed and destroyed by the Japanese in the attack on Pearl Harbor, which prompted the U.S. to enter World War II.

In addition to its role in the nation’s military history, the Navy Yard provided Brooklyn with a huge number of jobs, as Europeans immigrated en masse via Ellis Island at the turn of the 20th century. Employment at the Yard spiked to 18,000 employees during World War I, and 75,000 during World War II—many of whom were women and minorities—who were able to break into shipbuilding industries for the first time.

After World War II, the Yard saw its relevance fade. A 1960 fire on an under-construction aircraft carrier killed 49 workers and caused $75 million in damage. Moreover, as the size of ships continued to grow, many newly constructed vessels were no longer able to clear the Manhattan or Brooklyn Bridges to dock at the Yard. In 1965, the Navy launched its last ship, and the federal government closed it down officially the following year, selling it to the city of New York.

Thousands of shipyard workers lost their jobs, and though the government offered relocations to other ports, many locals didn’t want to leave. “What the hell,” an Italian-American electrician from Williamsburg told the New York Times at the time. “I’m an old Grand Street boy. Why do I want to go to the shipyard out by Seattle?”

In the years after the closure, planners, engineers, and politicians suggested a variety of options for what to do with the Yard’s 300 acres of prime waterfront real estate—from a car factory to a federal prison to a massive garbage incinerator—but none of these came to fruition. In the late 1960s, the city created a nonprofit to manage the property. Seatrain Shipbuilding, a major builder of oil tankers, became the Yard’s biggest tenant, but ultimately the size limitations imposed by the bridges curtailed business and Seatrain shut down operations in 1978. The 30,000 to 40,000 jobs that had been promised never materialized.

The 1980s were depressed years for the Yard, and crime was rampant. According to long-term tenants, the Navy Yard “begged” industrial companies like manufacturers, wholesalers, warehouses, and trucking companies to rent space. “Nobody even wanted to come to the neighborhood,” a trucker who rented space at the Yard told the Times. “It was a war zone. We heard gunshots every night.’’

It was in the 1990s when the Yard began to be activated once more, when small manufacturers, fabricators, designers, and artists moved in. Robert De Niro proposed bringing a Miramax movie studio there in the late 1990s, but that plan was scrapped. Ultimately that project was awarded to Steiner Studios, which opened the soundstages on which shows like Girls and films like Sex and the City 2 would be shot.

Under mayor Michael Bloomberg in the 2000s, the city allocated $71 million to fix infrastructure at the Yard, which Bloomberg said was “bursting at the seams” with new business. The Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation, which manages the property, began major renovations in 2011 and announced a $2.8 billion master plan last year that will add more than 5 million new square feet of space.

The number of companies calling the Yard home jumped from 230 in 2007 to 330 in 2015. The media hailed it as the Yard’s largest expansion since World War II. In 2012, Brooklyn Grange opened an enormous rooftop vegetable farm there. In the years since, other notable food and beverage businesses have moved in, including the whiskey brand Kings County Distillery, the beloved bagel baker and fish smoker Russ & Daughters, and (soon) the grocery store Wegmans.

In recent years, the Yard has become a dynamic hub for technology, not just to be developed and manufactured, but also to be tested. In August, the Yard became the first place in New York City where you can hitch a ride in an autonomous vehicle—if you take the ferry there, a driverless shuttle will pick you up for free. Before that, the original Citi Bikes were piloted at the Yard before they ever saw the streets of Manhattan.

These days, 10,000 workers at 400 companies call the Yard home. With WeWork’s opening today, thousands more will join them.

Zak Stone is a writer in New York. His work has appeared in The New York Times, Fast Company, Bloomberg, and more.