If you’ve ever sat in a Womb Chair or marveled at the period styling of the Mad Men offices, you’ve seen the design influence of Florence Knoll Bassett, a pioneer of American modernism, who passed away in January at age 101. An architect and designer who worked deftly across media, Knoll Bassett—born Florence Schust, and known to close friends as “Shu”—had a rare seat at the table in a time when the design and architecture industry was even more heavily male-dominated than it is today. She remains an inspiration for her countless contributions to design. Below are just a few of Knoll Bassett’s lasting influences.

Her furniture designs exemplified the ethos of 20th-century modernism

Knoll Bassett was the creative force behind Knoll Associates, the design company and furniture manufacturer founded by Hans Knoll, whom she married in 1946, becoming partners in both life and work. After his untimely death in 1955, Knoll Bassett stepped up to take the reins of the company, serving as president until 1960, and director of design until 1965, when she retired.

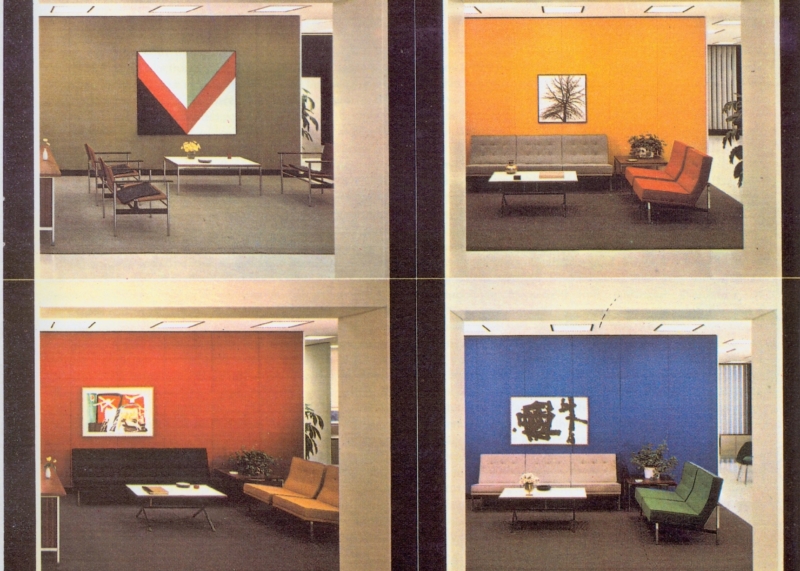

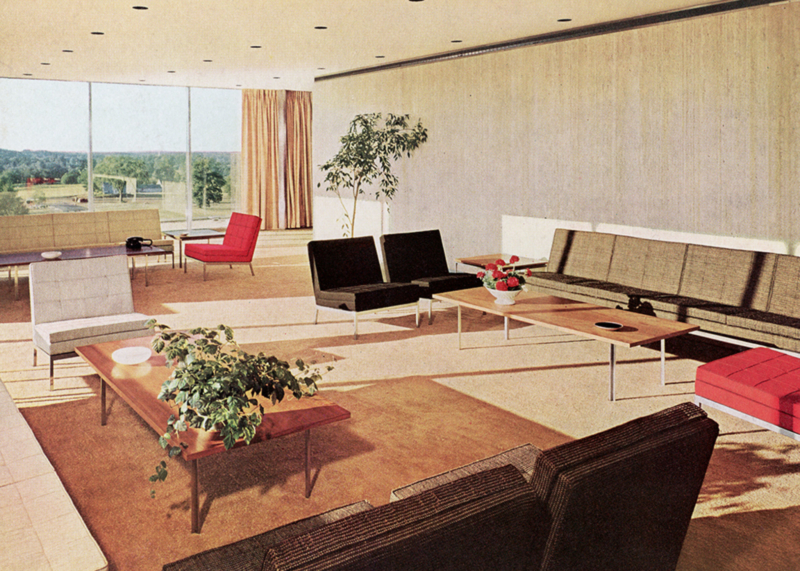

Her classic furnishings from this period channeled International Style architecture—precise, spare rectilinear forms with a visual lightness—at an intimate, human scale. While these early works have since reached iconic status, Knoll’s initial goals were less lofty. She referred to her stylish yet highly sensible range of sofas, desks, and tables, which comprised nearly half of the company’s collection, as the “meat and potatoes” basis needed for furnishing the modern home or office.

The spare, geometric minimalism of Knoll’s functional designs, while modestly conceived as “background architecture” for the modern workplace, resonated with the modern era—and replaced the stuffy traditional pieces that were ill-suited to the midcentury boom of high-rise office towers and glass skyscrapers. Today, Knoll Bassett’s furniture designs are held in the permanent collections of several museums, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Musée des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, even as many of these seminal works have remained in continuous production. Others, such as the Hairpin Stacking Table (based on her Model 75 stacking stool, first designed in 1948), have recently been reintroduced and brought back into production.

She shaped the look and feel of the postwar American workplace

To Knoll Bassett, furniture was but one element of an all-encompassing whole. In 1945, she significantly transformed the look of the American office with the founding of the Knoll Planning Unit, an in-house architecture studio that consulted on space planning for Knoll’s corporate clients. Together, the small team planned and designed corporate headquarters for companies such as Seagram’s, IBM, CBS, GM, and Look magazine—all of which occupied some of the era’s most innovative buildings—with the assertion that modern buildings necessitated modern interiors.

These projects presented an optimistic reworking of professional workspaces, channeling transparency, order, and flexibility in a contrast to the dark, heavy interiors of the past. The far-reaching influence of the Planning Unit, which came to be known as “Shu U,” also served as a de facto incubator for young designers who would go on to other architecture firms and start in-house interior design divisions, similarly modeled around Knoll Bassett’s pioneering approach.

She raised the bar for design retail

In 1947, Knoll Bassett was inspired to establish what’s now known as Knoll Textiles. “It became apparent to me that suitable textiles were not available for our furniture and interiors,” she wrote, matter-of-factly noting a void in the market for custom upholstery that could work with the pared-back style of modern furniture.

Launched with fabrics drawn from men’s suiting, the collection elevated contract furnishings and, with the addition of signature offerings, led to the opening of a dedicated textiles showroom that raised the bar for design retail. Designed with Herbert Matter, the displays featured cardboard-backed swatches and an immaculate gridded display of the division’s many textiles—retail innovations that quickly became the industry standard, admired and emulated by competitors.

She brought us works from some of the midcentury era’s greatest designers

Orphaned at a young age and taken under the wing of the Finnish-American architect Eliel Saarinen and his family, who became lifelong friends, Knoll Bassett’s personal life was intimately intertwined with some of the midcentury era’s greatest designers and architects. Through her work at Knoll, she not only commissioned a number of classic works by these 20th-century masters, but visibly credited, licensed, and established royalties for designers, a model that has since become de rigueur.

Anyone with a passing interest in design would recognize many of these famous chair designs, which have remained in production for decades. Among these are the classic wire-grid chairs by Harry Bertoia, a sculptor and classmate of Shu’s from the Cranbrook Academy of Art; and the sinuous, enveloping Womb Chair by Eero Saarinen, son of Eliel, and a close friend since childhood. She also brought into production the steel-and-leather Barcelona chair, which originally debuted at the 1929 Barcelona Pavilion by Lilly Reich and Bauhaus master Ludwig Mies Van Der Rohe; the latter was a mentor and teacher whose work heavily influenced Knoll Bassett’s own.

She was an active example of “total design”—and an inspiring figure behind many firsts

Knoll Bassett eschewed gendered roles and practiced “total design”—an approach that considered all parts and elements of an environment in its entirety—fully in her multidisciplinary work, which spanned architecture, workspaces, interiors, furniture, textiles, graphics, and retail spaces.

As Knoll Bassett firmly and famously asserted in a 1964 New York Times profile, “I am not a decorator.” Her drive and talents pushed the rigor and range of modern design—as well as a path for women—forward in history. As the same Times piece noted, she was “the single most powerful figure in the field of modern design.”